The social and scientific values that shape national climate scenarios

Cultural differences explain diversity of climate science for decision-making

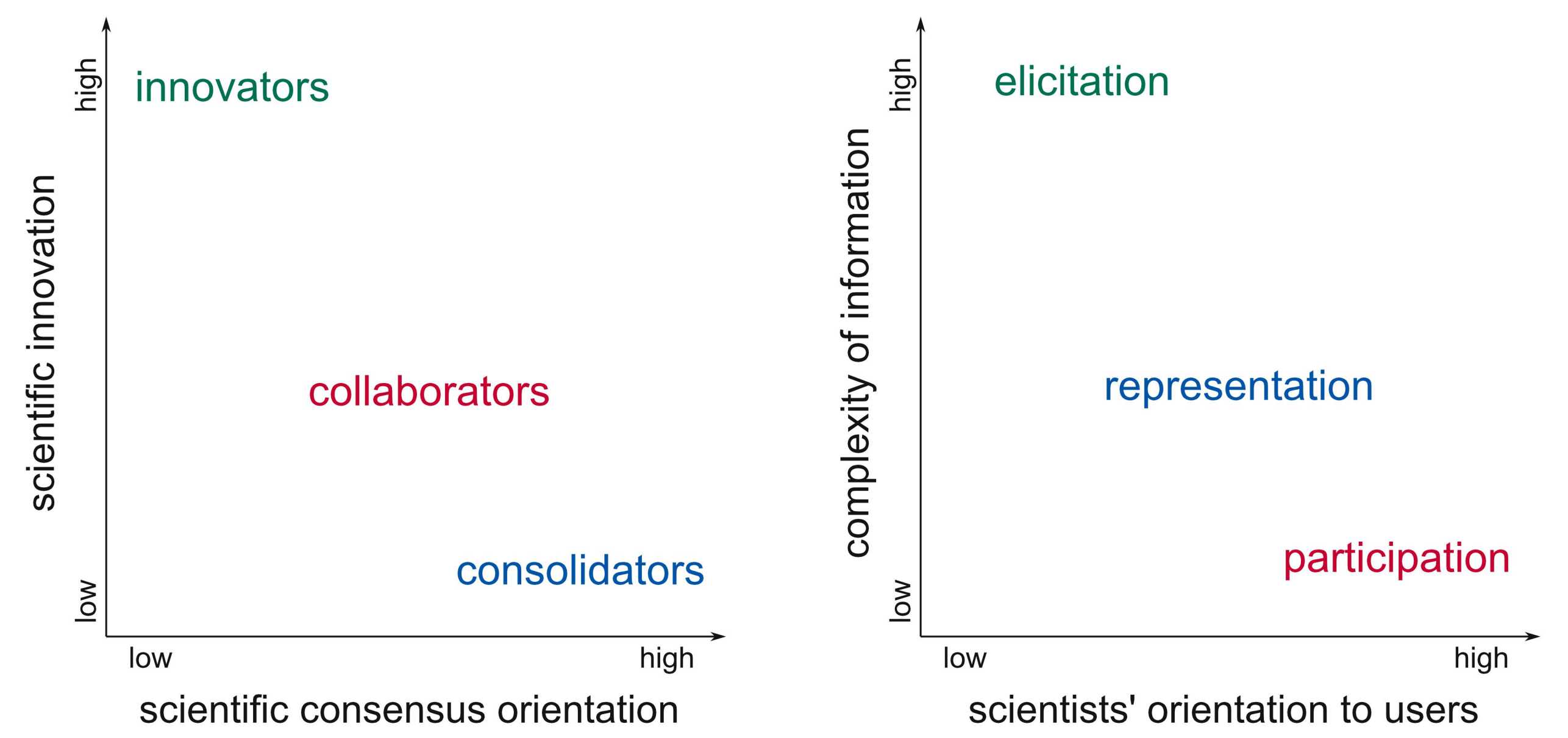

British, Swiss and Dutch climate scientists judge the usefulness of climate information for decision-making differently. For innovators, the newest climate science is seen as essential for decision-making (UK). This includes developing novel methods to derive new estimates of future climate changes, and communicating the data-heavy product as probability density functions. However, less sophisticated and less numerate users of the climate scenarios struggle to understand these probability density functions.

Consolidators, on the other hand, believe that only tried-and-tested knowledge should be used to make decisions (Switzerland). The Swiss climate scientists emphasised peer-reviewed material produced not only by themselves, but reported it only when similar findings were established by their international colleagues. While this approach is much in line with the IPCC process of reporting only consensual knowledge, it also led to certain information being held back. For example, the Swiss climate scientists chose not to communicate climate scenarios for the Alpine region due to the complex topography. Unfortunately, the Alpine climate will change significantly in the near future. Snow lines will ascend and permafrost will melt. And so the many requests by users led to a special report being issued.

And lastly, collaborators want to tailor their findings to their users’ needs as much as possible (Netherlands). To achieve this, the Dutch climate scientists engaged in many face-to-face interactions. They did not hold lectures. Rather, the scientists listened to the challenges the users faced. For the Dutch scientists, it was key to understand the situation the users were in. And to then give the adequate information. For the Dutch, it was clear that easy-to-understand storylines of future climates was the way forward. ‘Half of the work was having conversations, half of the work was the modelling’, one scientist said.

This diversity is surprising given there are so many similarities in the way the UK, Switzerland and the Netherlands model the climate. All these climate scientists work in esteemed climate science universities or met offices. Many are leading climate scientists in their field. And yet the climate scientists produced nationally distinct climate scenarios. The different epistemic preferences of innovators, consolidators and collaborators lead to climate science being communicated differently.

Interestingly, the three types of climate scientists interpreted the role of stakeholders in producing climate knowledge differently, but in line with their preferences. Innovators are the least keen to engage directly with stakeholders. Their quest to find academic novelty and advance science does not align well with responding to users’ wishes. In the British example, selected users received surveys on their needs. In addition, climate scientists gave lectures to them. But in this elicitation process, the incorporation of feedback from users was limited. This contrasts strongly with the Dutch approach, where collaborators interact with a variety of different stakeholders in an equal partnership. Scientists listen and respond to both knowledgeable and less experienced users in a partnership. But this kind of participation works only when climate scientists want to engage in such an equal way. And the consolidators have yet another relationship. The Swiss climate scientists consulted two representative users directly, discussing both scientific and communication issues. These representatives came from a civil society organisation and a climate impact modeller well accustomed to the agricultural sector.

But why did these climate scientists working in three different countries judge the usefulness of climate information so differently? Why such a diversity in the way users were included in the production of the climate information? When the picture is enlarged to include as well the different politics and government styles in the three countries, it becomes clear why climate information is judged ‘useful’ differently by innovators, consolidators and collaborators. Climate scientists in the UK are expected to have different roles than their counterparts in the Netherlands or Switzerland. But is it really that surprising that Swiss climate scientists emphasise consensual knowledge? Or that the participatory style of Dutch politics expects that Dutch climate scientists need to have face-to-face interactions with users? Not really.

‘I know now why British and Dutch climate scientists do things differently to us, in Switzerland’, a Swiss climate scientist exclaimed when we pinpointed to the underlying reason of the diversity. So what does this mean for the similar future of such projects? Because climate scientists respond subconsciously to their national political culture, we should not simply cut-and-paste ‘best’ practices from one country to the next. It can lead to frustration for both scientists and users. And the produced knowledge may remain unused by policy-makers and planners. To avoid this, scientists and users need to start reflecting on their information and interaction preferences. Our typology is a good starting point for scientists wanting to produce knowledge for decision-making. So ask yourself: Are you an innovator, consolidator, or collaborator? And do you want to interact with users through elicitation, representation, or participation?

Original research article:

Skelton M., Porter J. J., Dessai S., Knutti R., Bresch D. N. (2017): The social and scientific values that shape national climate scenarios: a comparison of the Netherlands, Switzerland and the UK. Regional Environmental Change. doi: external page10.1007/s10113-017-1155-zcall_made